What is Trauma?

The American Psychological Association (APA) defines trauma as "an emotional response to terrible event like an accident, rape or natural disaster." The effects of trauma can be widespread and long-lasting; for example, a trauma survivor might "shut down" in a stressful situation, have difficulty expressing emotions, and/or relive the trauma over and over again.

What does it mean to 'work with trauma'?

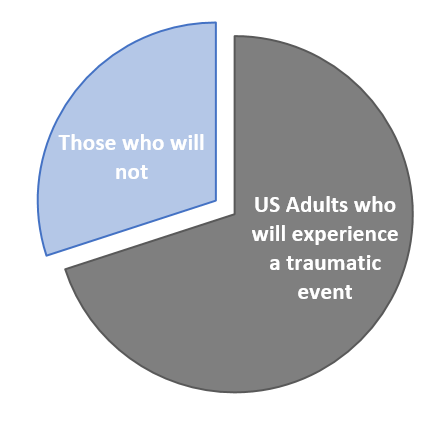

Some organizations work directly and explicitly with trauma survivors as a part of their core mission (e.g. foster care organizations, veteran services, crime-victim advocacy groups). However, it is impossible to tell just from looking at someone whether or not they have experienced trauma. Given the prevalence of trauma (some estimates suggest that 70% of adults in the US have experienced a traumatic event in their lifetime), all organizations can benefit from considering its effects when designing new policies, procedures, or programs.

So: If trauma is so important to consider, how do we integrate it into research & evaluation?

One of Flux's guiding ethical principles is to protect the interests of vulnerable stakeholders, who may or may not be directly involved in the evaluation process. One way that we can do this is to adopt a trauma-informed approach to research and evaluation. Here's what this might look like in practice:

1. Educating ourselves about trauma:

Ideally, everyone involved in a program evaluation would become informed about the impact of trauma, as well as any specific known issues and triggers for participants. We must learn to recognize the signs and symptoms of trauma and continually refine our evaluation plans to take survivors' experiences into account.

2. Ensuring participants' safety:

One foundational principle of trauma-informed care is to create spaces that are both physically and emotionally safe for participants. If conducting a focus group, for example, the facilitator should check the space ahead of time to make sure it is clean and free of hazards. During the focus group itself, the facilitator must intentionally build a rapport with participants and monitor the group's dynamics, intervening immediately if something inappropriate is said or done.

Another safety concern relates to confidentiality; we must protect our participants' identities and take the time to explain our confidentiality procedures. What participants say during an evaluation should never be able to be used against them by program staff, supervisors, or fellow clients.

3. Obtaining informed consent from participants:

At the beginning of any research process, we outline the potential benefits and risks to participants. By being as transparent as possible, we can let people know exactly what will be expected of them and alert them to any potential triggers ahead of time.

Participants need to know that they can opt out at any time. It may be helpful to check in with participants at multiple times just to see how they are doing and ask if they still wish to continue. This gives them control and a sense of choice, both of which promote well-being for trauma survivors.

4. Carefully designing data collection instruments:

We must be attentive to the way survey and interview questions are worded and structured; even a seemingly routine question, such as one about gender identity, has the potential to provoke post-traumatic reactions for transgender participants if they do not fit into the answer choices given. Other, more obviously sensitive questions (i.e. about sexual behaviors or military history) should be handled with utmost care and reviewed by stakeholders who can offer feedback.

During an interview or focus group, the facilitator should actively look for signs of a posttraumatic response to the questions being asked and be prepared to respond in a supportive way.

Because

of the way that trauma affects the brain, a survivor may literally be unable to "think about" or verbally process their experiences.

For example, a participant might become visibly agitated, speak more quickly, cry, or even detach from the questions. Because of the way that trauma affects the brain, a survivor may literally be unable to "think about" or verbally process their experiences. Silence during an interview, therefore, could be a sign of re-traumatization rather than an unwilllingness to participate in the process; instead of pushing for a response, the facilitator might instead choose to stop and re-establish a safe rapport before continuing.

5. Elevating participants' voices throughout the evaluation process:

Trauma-informed care is fundamentally a strengths-based approach that aims to empower participants in their own healing process. We can support their healing by giving them autonomy and actively listening to their concerns and ideas. Instead of asking "What is wrong with you?" we can ask "What has happened to you?," creating a space for them to share their stories. Where possible, we try to gain participant input, from the original research design to the final sharing of results. Ultimately, we believe our evaluation is stronger when we take into account not just the trauma that our participants have experienced, but also their diverse strengths and experiences.

More to explore:

Have you adopted a trauma-informed approach in your work? If not, what first steps might you take? Continue the conversation in the comments below!

This post was written by Callie Dean, our newest Flux Associate.

Check out more about her on the Flux website: http://www.fluxrme.com/about

Or, email her at callie.b.dean@gmail.com